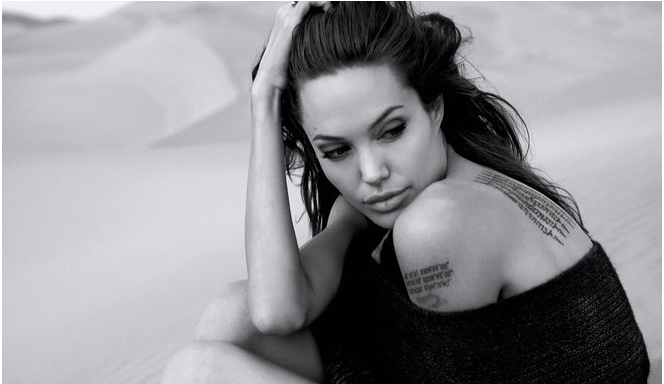

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz, Vogue, November 2015

Angelina Jolie Pitt is calling the shots as actress, mother, philanthropist, and auteur. Next month, she and her husband, Brad Pitt, will appear as a married couple in By the Sea, which she wrote and directed and is their first on-screen outing since Mr. & Mrs. Smith.

“The director was very focused. The actress was unstable. And the writer was deeply confused,” says Angelina Jolie Pitt. Then she laughs. She’s talking about what it was like to direct herself and her husband as a married couple in her own script for By the Sea, an elegiac exploration of grief and love. Ten years after her last collaboration with Brad Pitt, Mr. & Mrs. Smith—the movie that sparked their relationship—it’s about as far from that marriage-as-war-of-assassins comedy as you can get.

“This is the only film I’ve done that is completely based on my own crazy mind,” she says, speaking with humor and intensity, bringing to life a soulless room at the Sunset Tower Hotel. Outside is glittering, heat-wave sun, umbrellas packing the Los Angeles beaches. Inside, Angelina’s in black—skinny pants, short-sleeved silk blouse—which makes her printer paper–white skin even whiter. She wears no makeup. Why bother? Her beauty has only deepened with time.

See Angelina Jolie Pitt and Brad Pitt Behind the Scenes in By the Sea:

For years, she says, she and Brad called the script for By the Sea “the crazy one. We even called it ‘the worst idea.’ ” She laughs again, and covers her face with her hands. “As artists we wanted something that took us out of our comfort zones,” she explains. “Just being raw actors. It’s not the safest idea. But life is short.” Angelina, of course, has never played it safe. And at this point in her mythic life, perhaps the only risk left is to pare down the myth, expose her self.

And so, after getting married the summer of last year at her house in France, she moved with her tribe (Brad, six children now aged seven to fourteen, and assorted staff) to the Maltese island of Gozo, a stand-in for the southern French coast with its dazzling Mediterranean light, and shot the film. “It was our honeymoon,” she says, with a wide-open smile that expresses all that’s left unsaid about the highly privileged carnival that is her life. “They travel like gypsies,” observes Angelina’s friend, the screenwriter Eric Roth, describing the family’s peripatetic lifestyle. A band of galactically famous multimillionaire gypsies.

The kids are homeschooled by teachers from different backgrounds and religions, speaking different languages. “We travel often to Asia, Africa, Europe, where they were born,” says Angelina. “The boys know they’re from Southeast Asia, and they have their food and their music and their friends, and they have a pride particular to them. But I want them to be just as interested in the history of their sisters’ countries and Mommy’s country so we don’t start dividing. Instead of taking Z on a special trip”—ten-year-old Zahara was adopted from Ethiopia in 2005—“we all go to Africa and we have a great time.”

When we meet, Jolie Pitt has just returned from Cambodia, the location for her next film, and Myanmar. She took along Pax, her eleven-year-old Vietnamese-born son, who wanted to work on the film and meet Aung San Suu Kyi. Pax had read about the liberated Burmese opposition leader and Nobel laureate and was curious. “Seeing Pax get extra-nervous about which shirt he is going to wear when he meets Aung San Suu Kyi, I get very moved,” she says. “He rightfully doesn’t get nervous going to a movie premiere; he gets nervous going to meet her.”

Since Jolie Pitt got back to their home in Santa Barbara—almost like any mother—she has had to attend to doctors’ appointments, vaccines for the kids, play dates, and meetings, before the whole troupe decamps again to their house in London. For now, it will make the best base for their projects. Angelina can travel to the Middle East on UN trips and to Cambodia to prep her film, and be back for the kids, and Brad can fly to and from Abu Dhabi to shoot David Michôd’s War Machine, adapted from journalist Michael Hastings’s account of America’s recent conflict in Afghanistan.

If her daily life is a large, sociable whirl, Angelina’s new film is an intimate, claustrophobic tale. She wrote By the Sea after her mother, Marcheline Bertrand, died of cancer eight years ago, and never thought it would see the light of day. She wanted to explore bereavement—how different people respond to it. She set the action in the seventies, when her mother was in her vibrant 20s, and began simply with a husband and wife. She gave them a history of grief, put them in a car, and drove them to a seaside hotel to see how the pair—Roland, a novelist with a red typewriter; Vanessa, a former dancer with boxes of clothes and hats—attend to their pain. Vanessa is frail, tortured, hemmed in. She feeds her mourning a diet of pills and suicidal fantasies. Roland is defeated by the seclusion of her anguish, and drinks. And so it goes on until innocent newlyweds move in next door. . . .

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz, Vogue, January 2007

“It’s not autobiographical,” says Angelina, smiling. She shrugs off the fact that celebrity-watchers will have a field day trying to read into this movie. “Brad and I have our issues,” she offers, “but if the characters’ were even remotely close to our problems we couldn’t have made the film.” Yet the film is a deeply personal project, drawn loosely from her mother’s life. Jolie Pitt often talks about the sacrifice her mother made in giving up acting to raise her and her brother, James, after their father, Jon Voight, left. Later Bertrand’s work was cut short as a producer and activist for Native Americans and for the Give Love Give Life cancer organization she founded with her partner, John Trudell. She was diagnosed with ovarian cancer at 49; she died seven years later. “My mother was an Earth Mother and the nicest person in the world,” says Jolie Pitt (pointing out that Vanessa in the movie is not). “But the specific grief came from the woman I was closest to, seeing her art slip away, her body fail her.”

She and Brad may have chosen to shoot this movie to challenge themselves, but it was during the editing that Angelina got the real scare. Her doctor called, saying she had elevated inflammatory markers. She consulted Eastern and Western physicians, including her mother’s former doctor. She had her ovaries and Fallopian tubes removed. She detailed her experience in a New York Times Op-Ed, fulfilling a promise to keep readers informed after relating two years earlier her decision—having learned she had the BRCA1 gene—to have a preventative double mastectomy.

“It really connected me to other women,” she says of her decision to go public. “I wish my mom had been able to make those choices.” The procedures themselves were, she says, “brutal. It’s hard. They are not easy surgeries. The ovaries are an easy surgery, but the hormone changes”—she laughs, nods her head—“interesting. We did joke that I had my Monday edit. Tuesday surgery. Wednesday go into menopause. Thursday come back to edit, a little funky with my steps.”

Jolie Pitt has famously said that she has a ticking clock in her head, and that she is surprised to still be here; that she lives every day like it might be her last. Now, having gone through menopause, she says, “I feel grounded as a woman. I know others do too. Both of the women in my family, my mother and my grandmother”—who also succumbed to ovarian cancer—“started dying in their 40s. I’m 40. I can’t wait to hit 50 and know I made it.”

All through our conversation on this cloudless L.A. afternoon, I’m aware of the vast landscape inside the easygoing person who sits before me, her tattoos visible, her jewelry minimal, with her aviator sunglasses, her pen and folder on the couch. Besides the actress, director, and outspoken cancer warrior, there are the other Angelinas—the most glamorous woman in the world who has to meet in an anonymous hotel room because she can’t go anywhere in public without being mobbed. “You cannot take AJ undercover,” laughs Zainab Bangura, a Sierra Leonean political activist and former government minister who is now the UN secretary-general’s Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict. “She says, ‘When can we travel together? Anything more I can do?’ I can run around in Somalia undercover, but you cannot hide AJ.”

There’s Florence Nightingale Angelina, Special Envoy of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, who travels constantly to countries in crisis, supports, negotiates, and interacts one-on-one. “The hug,” says Bangura, “is powerful for people in pain. They know she’s genuine.” She can use her star power to make demands—to see a president, speaker of Parliament, and defense secretary, as she did recently in Myanmar to convince them to let her travel by helicopter to visit the Rohingya, a Muslim minority group facing ethnic cleansing. (A cyclone hit, and her trip was canceled; but she will go back.) And there’s the CEO Angelina, a Hollywood powerhouse who, like a martial artist, tries to wield the system to her advantage: outwits the gossip magazines by selling the first pictures of baby Shiloh in 2006 for a reported $7.5 million, and of her twins, Knox and Vivienne, born in 2008, for double that, donating the money to the Jolie-Pitt Foundation; earns a fortune playing assassins and superheroes, then making more mission-driven films, like A Mighty Heart, Beyond Borders, and In the Land of Blood and Honey; satisfies her fans with her poise and beauty while acting out her ambitions for a committed life on a global stage.

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz, Vogue, November 2015

I’m also thinking of the other Angelina, the younger one, the awkward kid who wore glasses and boxed, the dark, wild punk who used to say anything, talked openly about cutting herself, collected weapons, flipped a butterfly knife on Conan O’Brien after she made Gia, sported a vial of her second husband, Billy Bob Thornton’s, blood.

That power of the raw was the first thing director James Mangold saw before her audition for Girl, Interrupted, her 1999 breakout movie, after Gia. “I met her at the Sofitel, where she was staying. I remember the first thing she said: ‘This place is so dumb and French country, and I hate French country.’ ” Mangold is still in awe of that audition. “I felt like I was looking at a ravishing female Jack Nicholson.”

What really set her apart? “Attitude. As directors we are starved for it in men and women,” he says. “We’ve all gotten so correct and polite and understanding of one another and the multiple points of view. And that is a good thing, but on another level it’s just a little harder to elbow your way out in front. It takes aggression, and attitude.” Clint Eastwood had it, he says. John Wayne, Humphrey Bogart, Barbara Stanwyck. And Angelina.

“I needed someone who questions the rules,” he says of Girl, Interrupted, “who fucks who she wants to, pushes aside who she wishes to, and speaks the truth as she sees it . . . to be such an outlier they are deemed sociopathic but to us, the audience, they are brilliant.” That was Angelina’s character. And, as Jolie Pitt has said, it was also a part of her. “She was trying at that time to navigate, with far greater success than the character, what is unique about her,” says Mangold, “while finding a way to integrate herself with all the pedestrian things we live with—like French country.”

Jolie Pitt used to have a window: a tiny box, tattooed on her lower back. As a kid, she says, and even on movie shoots or with her former husbands (Jonny Lee Miller and Thornton), she used to stare out windows, longing for a life elsewhere, thinking, There has to be something else.

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz, Vogue, November 2015

That turbulent and restless 25-year-old was the one who traveled to Cambodia to make Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, the video-game heroine saving the world’s light from the forces of darkness, and had her eyes opened by the devastation wrought by the Khmer Rouge. She was confronted by genocide, refugees, people with prosthetic limbs, land mines still ripping apart children at play, the whole constellation of war’s consequences and injustices.

Cambodia reshaped the contours of Jolie Pitt’s life. As she’s said, if someone had dropped her at fourteen in the middle of Asia or Africa she’d have realized how self-centered she was, that there was real pain, real death, real things to fight for. She came home, made phone calls, read everything she could get her hands on, and began traveling with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees on her own dime to figure out how she could be of use, bringing along her notebook and a willingness to sleep anywhere and take physical risks. Returning to Cambodia soon after she finished the movie, she kept a journal, later published as Notes from My Travels, in which you can witness her transformation taking place:

Friday, July 20, 2001, in Cambodia: “On my way to my room I couldn’t help but notice all the bomb casings. . . . These weapons and explosives were originally made by manufacturing plants run by governments like mine.” She goes out with the deminers to find out how they work. “Two land mines were discovered. I was allowed to detonate one of them with TNT. I must say it was a great feeling to destroy something that would have otherwise hurt or possibly killed another person.” In a former Khmer Rouge prison she writes, “In each one of the cells there is a picture of the person who was tortured. . . . As I continue to write this I think, What am I doing? How can I be standing here?”

In her travels with UNHCR she finally flew through the window. She even had a former Buddhist monk in Thailand tattoo a tiger over it. And she took the fight against herself and turned it on injustice. As she writes about the refugees she meets, “I wanted to help them, and I realize more and more every day how they have helped me.” She also realized fairly quickly that she could take the Hollywood insanity, the fairy dust, the massive power and money she was accruing with blockbuster franchises like Lara Croft and, later, Maleficent, and use them, her way. She wasn’t just going to play Lara Croft, she wanted to be a kind of Lara Croft and change the world.

Phillip Noyce, the director of Rabbit-Proof Fence and The Quiet American, worked with Jolie Pitt on The Bone Collector back in 1999 and then on the action movie Salt in 2010. He puts it rather beautifully when he says, “She has a hard back and a very soft front. The back is determined. The front is soft and receiving of ideas.” On Salt, she demonstrated her stubborn desire for authenticity. At one point, he recalls, Salt had to escape from her apartment. Noyce told Jolie Pitt that he’d make a green screen ten feet off the ground to look as though she was eight stories high. “She turned to me and said, ‘No, no, no, I want to be out there.’ I said, ‘You don’t need to. It’s very dangerous. Why?’ ‘I’ll act much better if I’m really out there, and it’s going to look better,’ she replied. Six weeks later she’s out there. She had learned that there’s too much CGI. The audience instinctively knows what a CGI shot is. They are sick of it.” Audiences want to see the real. That was her point. “When she is working, she is a conductor of ideas. They flow through her like electricity and emotion,” Noyce says.

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz, Vogue, November 2015

Last April, Jolie Pitt watched her now nine-year-old daughter Shiloh among refugees in Lebanon. “When she was sitting on the floor with her UN cap writing her notes as she was talking to someone, I was flashing on myself fifteen years ago and thinking, I know that moment,” she says. But she also knows that it may not be the same for all her children, and she doesn’t push. The Jolie-Pitt world is democratic, eclectic. “The kids that don’t want to go don’t go,” she says of her humanitarian field trips.

The $20 million–plus Jolie-Pitt Foundation she created with Brad in 2006 now funds clinics and schools in Ethiopia, Kenya, Afghanistan, and Cambodia, as well as lawyers for unaccompanied immigrant children in the U.S., demining programs, and environmental and wildlife conservation. And Jolie Pitt’s work with UNHCR is ever-evolving. I speak to the high commissioner, António Guterres, who has one of the toughest jobs on the planet at this moment and gets right to the point. “Let’s be honest, people do this to benefit their image,” he says. Not her. “When I try to make what she does more public, she is always very shy. She prefers to be with refugees, visit the families and do it without media. Which I tell you is uncommon,” he says quickly. “As you know, many celebrities are weak on details of the problem, and the devil is in the details.” The people she meets—mayors, local officials, whoever they might be—“They’re surprised that someone like her comes and discusses the problem of the bathrooms.”

It’s the Angelina effect, one that can also make critics roll their eyes when she seems to be everywhere at once. While that may be the case, she doesn’t suffer from the familiar “five-minutism” of celebrities showing a fleeting interest in global causes. In fact Jolie Pitt is vigilant—she resigned from the U.K.–based mine-clearing charity, the Halo Trust, when it was discovered that funds had been misused—and doesn’t let an issue drop. Laura Silber, coauthor of The Death of Yugoslavia, recalls her skepticism when she was first contacted to help with accuracy on Jolie Pitt’s directing debut, In the Land of Blood and Honey, about the Bosnian War. “Most Hollywood people don’t have a sustained interest in an issue,” she says. “But after the movie, Angelina wanted to understand the roots of the conflict and how she could leave a lasting contribution to change lives—which she did. That really set her apart.”

I catch up with Jolie Pitt again by phone in London on September 4, two days after Alan Kurdi, a three-year-old Syrian Kurdish boy, washed up on a Turkish beach, and the image of his little body was shaming politicians and breaking hearts all over the world. As special envoy on refugees, I ask her, what do you do in the midst of this crisis? She hesitates. She’s upset, like anyone, but isn’t shocked. She’s been testifying to the Security Council and advocating for Syrian refugees for the last four years. “Part of my day today is hours of discussion in the office to try and communicate not just concern but coherent ideas,” she says. Three days later, she will publish an Op-Ed coauthored with Arminka Helic—a British member of the House of Lords and former Bosnian refugee—calling upon the public to prioritize Syrian refugees and to pursue a diplomatic end to the war with the same vigor with which they pursued the Iran nuclear deal.

We talk about the personal connections she has made with families, friends all over the world, and how to navigate the complexities of “help.” “In a strange way I don’t think about it as helping my child or someone else’s child,” she says. By way of example, she talks about an initiative that started in 2003. “I went into Cambodia to put aside a little place for Maddox”—her fourteen-year-old, whom she had adopted from Cambodia the year before—“and do a little community development,” she says. When she found out that poachers were destroying the wildlife in the neighboring Samlout national park, she started a conservation program and hired the poachers as rangers. Within a few years she had created schools, roads, and clinics, and experimented with economist Jeffrey Sachs’s ideas for Millennium villages designed to help break the cycle of poverty.

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz, Vogue, November 2015

It is mind-boggling to think of the numbers of projects emanating from her office. How does she juggle films, humanitarian work, speeches, husband, six children? (Named an honorary dame by Queen Elizabeth II, she will be addressing the House of Lords in a few days on the subject of sexual violence in warfare.) “I schedule individual time with each of the kids like a crazy person,” she says. “I know what I’m doing with my boys tonight”—her friend Mariane Pearl, whom she played in A Mighty Heart, is on her way over with her son, Adam. They’ll go out and then “play board games all night.”

Recently, Jolie Pitt says, she was working with her voice coach for Maleficent in an office in her house. “I closed the door. One kid came in and another came in and there was a fight outside the door.” A few weeks later, Brad was using the office, “so I did my voice lessons in the center of the house in full view on the kitchen table. And nobody bothered me. Not one interruption.” She laughs a long time on the phone. “It was very clear to me that if they can see you and hear you and you’re right in the room, they actually give you a certain space.”

Being at the center of everything seems to be the place where Angelina thrives. And yet her growing influence in her many spheres of operation carries its own risk of compromising the fiercely independent spirit that got her here. Being the leader of Angelinastan, a place of art and humanitarianism, decadence and generosity, politics and power, requires a certain megalomania, unstoppable ambition, and a need and ability to control the plot. “She’s not easy, but easy is overrated,” observes Mangold. Power is a tricky thing—you need it to have an impact on a global scale, but what sacrifices will she have to make for the sake of diplomacy?

The coming months will see her moving forward with her Cambodian film, for which she will spend time in schools and orphanages playing games with kids to find a seven-year-old lead for her adaptation of Loung Ung’s memoir First They Killed My Father. It’s Ung’s childhood story of torture, death, and survival under the Khmer Rouge. She had sent the book to Angelina shortly after she returned from filming Lara Croft: Tomb Raider and was speaking out about land mines. They became fast friends, and it was Ung—orphaned by the Khmer Rouge—to whom Jolie Pitt turned to ensure she was doing the right thing when she decided in 2001 to adopt a baby boy she’d met in an orphanage—the young Maddox. The movie, on which she has teamed up with award-winning Cambodian filmmaker and archivist Rithy Panh, will be her love letter to the country that changed her life and of which she is now a citizen. “It’s a very unusual film,” she says. “There’s not a lot of dialogue. A child experiences more than she talks.” The film will be in Khmer; the wardrobe will be made in Cambodia. “I’ll be making it with the Cambodians every step of the way,” she says. It’s her insurance policy against any unintentional disrespect. “I will feel the ghosts of a million people who died. It’s their story and their skulls in the ground. And that is a great responsibility.” Maddox will research archives and history and work on the shoot. “So will Pax,” she adds. “The film will change Mad, but as much as he’s discovering the horrors of the past, he’ll also be discovering the culture before the war, the dignity of his country, how they held their heads up.”

She has also been trying to develop a film about the Kenya-based wildlife conservationist Richard Leakey. Here, you see how the worlds she straddles offer her different routes to the same end. If the project doesn’t pan out, she says, “I can work with Leakey and do just as much good.” And then there’s Cleopatra, based on Stacy Schiff’s 2010 history. It was the movie at the center of the scandal of the hacked Sony emails, in which it was described as a “$180m ego bath” for Angelina. (“I was enraged,” says Eric Roth, the screenwriter on the project, “but she has enough confidence that she didn’t engage in any of it.”) As Jolie Pitt says, “It’s a hard one to get right. It needs to be about something other than sex and jewelry. She was a very complicated leader of a country.” She’s interested in Cleopatra as an astute politician, says Roth, in her humanity, how she relates to her children and the people of Egypt; you can see why Angelina would want this role.

Angelina doesn’t see herself acting forever. “What a crazy job!” she says. “I’m almost enjoying it more now that I see it as something I’ve been fortunate to be part of. Maybe in the next few years I’ll finish being in front of the camera. I’ll be happier behind it,” she continues. “I’m happy to be home. I want to really focus on my children, doing the best I can to guide and protect them before they are out of the house. These are their most important years.”

Star is really the wrong word for Jolie Pitt. It implies a fire millions of miles away, and though she loves to fly her Cirrus SR22, she is focused, pragmatically so, on earthly ambitions and earthly troubles. Much has been speculated on the growing political role she seems to be moving toward. She has formed JP.D.H London, a slightly unorthodox non-profit, with Chloe Dalton and Arminka Helic, whom she met when they were advisors to British Foreign Secretary William Hague and working on the initiative to prevent sexual violence in conflict. She is careful in how she characterizes the next phase in her career as non-state actor on the international stage, but it’s clear she’ll never stop testing herself. “I’d like to be part of international work, and see where I can be useful, whatever way that takes shape” is all she will say. “I still don’t know what I’m capable of.”